You’re doing everything right—working, studying, staying informed—but life

still feels rigged. Wages stagnate. Rents soar. Public services crumble.

Politics feel like theatre. It’s tempting to think the system is broken. But

what if it’s not?

What if this is exactly what the system was rewired to do?

This essay reframes what looks like failure as structure—how inequality,

instability, and institutional decay aren’t accidents but outcomes. And how

that system, built around asset appreciation rather than public value,

continues to perform well—for those it was redesigned to serve.

Why things feel like they’re falling apart

We’re told to work hard, stay in school, buy in. But that story—where effort

leads to security—doesn’t hold anymore. For many, wages aren’t rising, housing

is unaffordable, and the future feels narrower than the past. It’s not just a

rough patch. It’s systemic.

The deeper engine behind the chaos

A few years ago, Alex Hochuli described what he called the

_Brazilianization_¹ of the West: elite impunity, decaying infrastructure, and

widespread informal work—symptoms long associated with the postcolonial Global

South, now appearing in Europe and North America.

But these aren’t cultural imports. They’re structural exports. We’re not

becoming like Brazil. We’re all converging on the same system logic: one that

rewards asset ownership, punishes labor, and treats public goods as private

opportunities.

Why owning matters more than earning

In today’s economy, value doesn’t come from what you do—it comes from what you

own. A home. A pension fund. A platform. If you rely on wages, you’re exposed.

If you own appreciating assets, you’re insulated. Productivity no longer

raises incomes. Political promises feel thin. The system rewards holding, not

contributing.

Cities aren’t neglected. They’re reprogrammed.

When capital drives planning, public interest comes second. Cities now optimize

for return, not need. Housing becomes an asset class. Transit must break even

or be cut. Infrastructure decays—not because of dysfunction, but because it

doesn’t produce short-term profit.

Why doing all the right things isn’t enough

The new economic divide isn’t between industries or job types. It’s between

those who can accumulate assets and those who can’t. A postgraduate with no

capital faces the same structural instability as a gig worker. This isn’t

meritocracy failing. It’s a meritocracy without a payout.

The state isn’t asleep. It’s serving something else.

States can move fast—when the markets care. Central banks stabilize capital in

hours. Infrastructure takes years. In Jackson, Mississippi, residents had no

safe water for weeks, while investor confidence went undisturbed². It’s not

incompetence. It’s alignment. Mariana Mazzucato calls this the

“de-risking state”³: strong for capital, weak for citizens.

Why people check out instead of speak up

Political disengagement isn’t laziness. It’s feedback. When people realize

voting changes little, they adapt. Hustling, ghosting, optimizing for survival

aren’t character flaws—they’re rational responses. Michel Foucault’s idea of

the _entrepreneur of the self_⁴ now describes most of us: performative,

responsibilized, and on our own.

The gig economy isn’t new. It’s just digitized.

The informal labor conditions long familiar in the Global South—no contracts,

no protections, inconsistent hours—now exist in app form. Uber, Deliveroo,

Upwork: precarity as a service. We didn’t import Brazil’s labor model. We

automated it.

Who’s really in charge?

Asset-first economies shift power from voters to markets. Bondholders

discipline budgets. Ratings agencies shape policy. Capital mobility undermines

sovereignty. This is sovereignty by subscription: you govern, but only if

investors approve. Stay solvent—or surrender control.

The future isn’t failing. It’s vanishing.

Zygmunt Bauman’s “liquid modernity”⁵ has become liquid legitimacy—a world

where institutions don’t collapse, they just dissolve. Local councils go

bankrupt while paying investors. Public services erode without drama. David

Harvey called this _accumulation by dispossession_⁶—extracting public value and

turning it private.

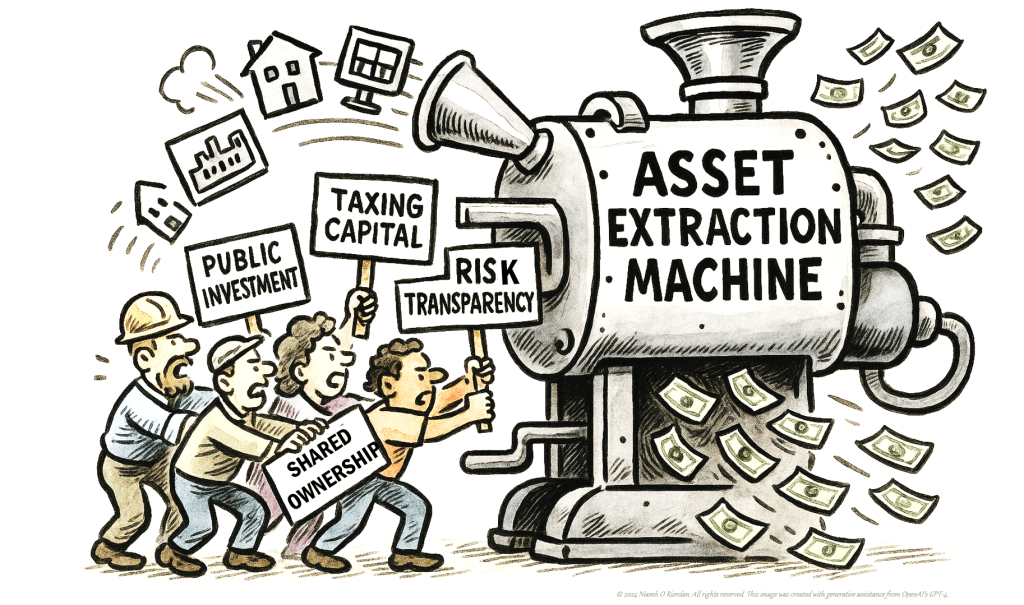

If this is the system—how do we change it?

First, revalue what counts. Thomas Piketty⁷ shows how inequality grows when

capital gains outpace wages. Taxing wealth like work isn’t radical—it’s

repair. So is treating housing as shelter, not speculation. So is defining data

as infrastructure, not property.

Second, change how we own. Shared wealth funds, municipal broadband, platform

co-ops—these models spread value instead of hoarding it. Mariana Mazzucato’s

_mission economy_³ says public investment shouldn’t just clean up after

markets. It should lead.

Third, make opacity expensive. Complexity fuels financial power. Transparency

shifts it. Demand systems that are legible to the public—not just analysts.

Finally, change the story. The old one said markets were rational, ownership

was merit, and wealth would trickle down. It hasn’t. We need a new story. One

where value is shared. Risk is mutual. And the future belongs to more than a

portfolio.

Curious about some of the terms used here? See the glossary below for a

plain-language guide to the system you’re already living in.

The Asset Economy: A Glossary of Terms You’ve Probably Lived Through

Asset Economy

The foundational concept of this piece: a system where economic power comes from what is owned, not what is done. As stocks, housing, data, and infrastructure become assets, labour becomes marginal. What looks like stagnation is often redistribution—upward.

Financialization

When everyday life becomes an investment opportunity. From housing to healthcare to higher education, value shifts from use to yield. Prices rise, access narrows, and complexity multiplies. It’s a system designed for trading, not living.

Entrepreneur of the Self

Borrowed from Michel Foucault. Describes how individuals are responsibilised to manage themselves like micro-enterprises. The line between person and portfolio dissolves. Selfhood becomes performance, and precarity becomes a brand.

Platformed Informality

A term used here to describe the digitised replication of informal labour conditions. The same low-rights, high-risk dynamics long associated with informal economies—now scaled and automated by platforms. No contracts, no protections, just “flexibility.”

Sovereignty by Subscription

Coined in this piece to describe the condition where national autonomy is effectively leased back from capital markets. Governments remain in charge on paper, but policy direction is shaped by bondholders, rating agencies, and investment flows.

Liquid Legitimacy

An adaptation of Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of “liquid modernity.” In this context, institutions do not collapse in scandal—they dissolve in irrelevance. Nothing settles. Nothing transforms. The erosion of authority comes not through crisis, but through fatigue.

Accumulation by Dispossession

A concept developed by David Harvey. Refers to how capital expands by enclosing and extracting from the commons. Public goods become private assets. Shared infrastructure is dismantled and sold back at a profit.

Mission Economy

Developed by Mariana Mazzucato. Describes a state-led model of innovation and investment, where public goals—not just market failures—set direction. Value creation is coordinated, long-term, and collective.

Public Investment

Used here to signal more than fiscal stimulus. True public investment means funding what markets avoid or degrade: universal care, climate adaptation, digital access. It’s not just about spending. It’s about designing for resilience.

References & Sources

- Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014).

- Hochuli, Alex. “The Brazilianization of the World.” American Affairs, Volume V, Number 2 (Summer 2021).

- Green, Emma. “Why Jackson’s Water Crisis Is a Warning for America.” The New Yorker, September 2022.

- Mazzucato, Mariana. The Entrepreneurial State and Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism (2021).

- Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979 (2008).

- Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity (2000).

- Harvey, David. The New Imperialism (2003).

© 2024 Niamh O Riordan. All rights reserved. This article was developed with generative assistance from OpenAI’s GPT-4. All ideas, perspectives, and final editorial decisions are the author’s own.